The spectacle of a filmmaker being violently ambushed by his subject is a compelling way for any documentary to begin; this is exactly what happens in the first minutes of ‘Beware of Mr Baker’ as legendary rock drummer Ginger Baker delivers a nose-breaking blow with his cane after taking exception to Jay Bulger’s intentions to interview people other than him in creation of this gripping biography. It is also an encouragingly early sign that this is no conventional music documentary and Baker, best known for providing the dynamic, virtuoso rhythms of 60s rock stalwarts Cream, is no ordinary character; even by the decadent standards of Rock n Roll.

The spectacle of a filmmaker being violently ambushed by his subject is a compelling way for any documentary to begin; this is exactly what happens in the first minutes of ‘Beware of Mr Baker’ as legendary rock drummer Ginger Baker delivers a nose-breaking blow with his cane after taking exception to Jay Bulger’s intentions to interview people other than him in creation of this gripping biography. It is also an encouragingly early sign that this is no conventional music documentary and Baker, best known for providing the dynamic, virtuoso rhythms of 60s rock stalwarts Cream, is no ordinary character; even by the decadent standards of Rock n Roll.

Music aficionados may or not be aware of Baker’s reputation as a cantankerous, irascible grouch but the attack on Bulger is a startling insight into a man who many regard as amongst the greatest drummers that ever drew breath. While those involved in the film express views that rarely exceed generous ambivalence in regards to Baker’s personality, they are absolutely unified in their convictions as to his prodigious abilities as a supreme percussionist. Contributing fellow drummers and musicians offer lofty praise ranging from “The world’s greatest drummer” to “A great virtuoso madman” and, perhaps most fittingly, Simon Kirke of Bad Company and Free summarises Baker as man and musician: “He influenced me as a drummer, not as a person.”

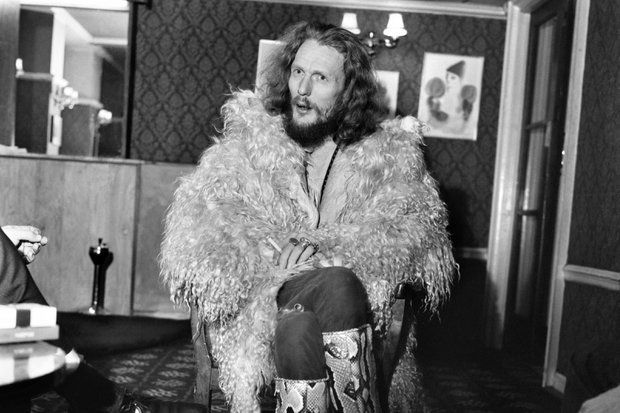

Combining effective animations with the more conventional narrative tools of photograph, video and talking-head, Bulger brilliantly captures the vertiginous whirl of Baker’s existence; a life so marked by extremity and tumult that it can hardly fail to entertain when assembled within a 90 minute film. Born into a Britain just weeks from entering the Second World War, he lost his father to the war four years later and was raised by a mother who later gave a teenage Baker ‘the strap’ upon discovering a record stolen from a local store in his bedroom. Importantly, the record in question was ‘The Quintet of the Year’ where Baker’s ears first became acquainted with the drumming of Max Roach; the discovery of his first hero and the subsequent lashing from his mother setting in motion a life’s cocktail of music and violence. A letter from his father, only to be opened once Baker reached the age of 14, hardly assuaged things with his advice “Use your fists, they are your best pals so often.”

Possessing what he describes as the God given gift of “Time,” Baker’s near instant precocious abilities were a passport to a lifetime of adventure; the first destination of significance being the basement flat of jazz drummer Phil Seamen who introduced Baker to both the polyrhythms of African music and the world of intravenous opiate abuse. As part of Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, Baker first met bassist Jack Bruce and thus began a fractious personal relationship heavily at odds with a musical harmony that proved both lucrative and enduring. Surviving fist fights and even an on stage incident where Baker pulled a knife on Bruce during their time in The Graham Bond Organisation, the two men ended up at “the forefront of a complete revolution of rock” when they formed Cream along with premier blues guitarist of the age, Eric Clapton. Incredibly, due to tensions between Baker and Bruce being so fraught as to occasionally reduce Clapton to tears, the lifespan of Cream was a mere two years. All too much for Clapton, he sought the refuge of a project with Steve Winwood only for Baker to turn up unannounced at an early rehearsal and the incorrigible wildman was back in his life as the drummer for Blind Faith.

Clapton speaks of Baker’s “compulsion” leading him to be extreme in everything he does; we learn that Baker had a heroin addiction that took him two decades to get under control and a keen tendency for Rock n Roll excess. His willingness to appear in Cream was dependent on a rider of “a case of beer, 2 black hookers and a white limo” while his decision to fly his car over to Jamaica is perhaps the first instance of a complacent belief in his inexhaustible wealth. Even a salubrious six year period in Africa where he collaborated in Nigeria with Fela Kuti, resulted in a voracious appetite for polo that would prove extremely damaging to the state of his finances. It is typical of Baker’s propensity for chaos that the relative sanguinity of his first African tenure ended up with a disagreement over a recording studio and his fleeing Lagos under a barrage of gunfire.

Interviewed at his gated compound in Tulbagh, South Africa, Baker is often contemptuous of Bulger’s enquiries; “What?! How I restrain myself from throwing things at you” he replies when asked if his Degenerative Osteoarthritis explains why he hasn’t played drums for several months. “Stop trying to be an intellectual dickhead” is another response given when unimpressed with the line of questioning. However, Baker’s scorn is by no means limited to filmmakers; he is scathing of comparisons to John Bonham who “couldn’t swing a bag of shit” and “Who is this stupid little cunt?” is his charming recall at his first seeing a young Mick Jagger. Baker, however, is visibly emotional when he describes Clapton as his “Best Friend on the planet” and even more so when recounting how he became friends with his four greatest drumming heroes. These are curious moments in the film; while revealing that tender emotions lie within Baker’s objectionable exterior, they paradoxically make him appear even more lamentable in view of the treatment inflicted on those who should’ve meant the most to him.

Now living with a fourth wife, Baker’s first marriage ended when he ran off with the seventeen year old sister of his daughter’s boyfriend and an approach of selfish negligence has seen him alienate his children. His decision to have thirty polo horses flown over to Britain from Argentina hugely impaired his finances and, with £150,000 being owed to the taxman, his first wife and children were left to roam the streets after the repossession of their house. It is with the unfeeling treatment of his son Kofi that Baker comes across as the most heartless; upon leaving the USA for the last time, Baker thought it an apt goodbye to tell his son that he was a shit drummer with abilities that would never match his own and, making clear his lack of feeling towards him, Baker walked out of his son’s life forever. Of course, this all makes Baker the most unsympathetic of figures but it is hard to subdue feelings of pity when Bulger asks him to remove his sunglasses and, in contrast to the wild-eyed youngster he once was, Baker reveals the dead eyes of a sick, ageing man; the relentless march of time perhaps the only beat that the great drummer couldn’t master.

Part of what makes ‘Beware of Mr Baker’ so appealing is its refreshing capacity to tell it like it is. There are no attempts to glorify or exalt and Bulger would clearly be hard pressed to present anything close to hagiography; of course, we have Baker to thank for this as he is clearly not a man to mince his words or indeed care about coming across as likeable. Also, Baker’s firm adherence to the Aleistair Crowley edict of ‘Do what thou wilt’ is such that it is difficult for those of us with more conventional and ordered lives not to derive a vicarious thrill from his adventures; really, how many of us have heard radio reports of our own heroin induced death while cruising along the Pacific Highway in a Shelby Cobra full of gorgeous groupies? While being a central player in his story would no doubt have led to exasperation, disloyalty, broken hearts or broken noses, the life of Peter Edward ‘Ginger’ Baker makes for one riveting view from the sidelines.

9/10

By Scott Hammond