Hailed as the “grandfather of modern dance music”, a “maverick, genius outsider” and “one of the most important people of 20th century music”, the sense of hagiographical terrain is abundantly clear in the earliest moments of Volker Schaner’s biography of Jamaican music producer and dub pioneer Lee “Scratch” Perry. It is, however, in both Perry’s scattershot self-regard and his likeable eccentricity that Schaner’s haphazard film mainly takes its cues. With no great care to intellectualise or understand, we are perhaps left with as slapdash and freeform a 97 minute piece as one would expect when focussing on an idiosyncratic star described in turn as “a madman”, “space traveller” and “mad professor”.

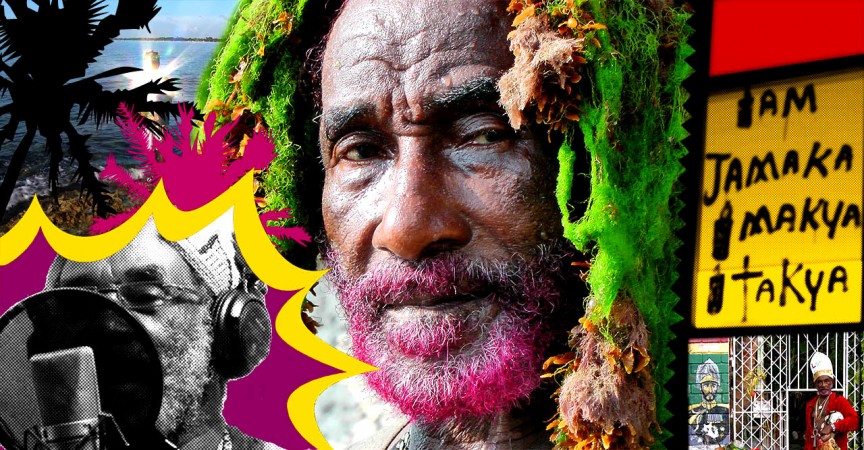

We follow Perry, alternately adorned in coloured permed wigs, his ornate baseball cap and his dyed purple facial hair, from his breathtakingly idyllic mountain retreat in Switzerland to the “Lion’s den” of London and back again to the Kingston neighbourhood that played host to the legendary Black Ark recording studios. It was here, modestly armed with limited and antiquated studio equipment, where Perry gained a vast reputation as a brilliantly innovative and unconventional reggae producer and, as a result, was sought out by superstar-in-waiting Bob Marley. We also learn that the conception of Black Ark studios was the result of Perry’s susceptibility to a shamanistic mythology that serves as a consistent focal point to his often opaque on screen ramblings: Perry maintains that a spirit told him to build the studio in order to “save” black people.

This sense of deliverance for his people is, however, not without valid motive and the film is perhaps at its most informative when describing the history of “divine and haunted” Jamaica. A “cornerstone of the capitalist system” due to the sugar and rum industries which enslaved the country during the British Empire, Jamaica became independent in 1962 and its people began the search for its own cultural identity. When a prophesy from Jamaican liberationist Marcus Garvey foresaw the coronation of a black king in Africa, it arrived in the apotheosis of Ethiopia’s Haile Selassie – a man viewed by the Rastafari movement as the “black messiah”. Perry subsequently became the first figure to turn the music of Rastafarianism into popular songs.

Being at the helm of a “musical revolution to solve the nation’s problems”, the film boldly equates Perry with Garvey and Marley with Selassie in painting a picture of comparative influence. Unfortunately, the film doesn’t delve anywhere deep enough to give any sense of these tumultuous times in Jamaican history and, unlike what Alex Gibney achieved in setting the scene of post-colonial Nigeria in his Fela Kuti biography Finding Fela, we are left with no real sense of Perry or Marley’s influence as figureheads for a struggling people. However, Perry leaves us in no doubt that his approach to music is that of a spiritual quest aligned with his Rastafarianism, his aims being to conquer evil with music and rail against the degenerative society of materialism and oppression referred to as “Babylon”. As with the themes of 1987 album Time Boom X De Devil Dead, Perry appears to be fighting a perennial battle to defeat the devil in all its forms, be it policeman, soldier, government or church.

It was after Perry’s falling out with Marley, and with the Rastas in a deep depression due to the disappearance of Selassie and a downward spiralling political situation in the late 1970s (again barely touched on), that the music shifted and dancehall took over. Adopting increasingly erratic behaviours, Perry grew into an isolated figure and, as is the subject of largely conflicting accounts, he infamously committed arson on his very own Black Ark recording studio. An end to an era facilitated by this bizarre act of pyromania, Perry later began to emerge more as a word association artist and poet – his stream of consciousness and fondness for rhyming and wordplay is a consistent feature of Perry’s contributions in front of the camera.

Despite the film’s formless meandering, dealing with someone as unique in character as Perry makes it an impossibility to be devoid of entertainment and interest. Though it feels refreshing not to dwell on Perry’s work with Bob Marley, the moments where their falling out is discussed capture the film’s subject seemingly at his most pensive – the section where Perry lambasts Marley as “extra greedy” is an interesting nugget of insight to their estrangement. Meanwhile, footage of a 2010 recording session with English electronic duo The Orb sheds light on Perry’s genial and often ramshackle inception of ideas. With a curious mixture of an almost childlike sense of fun and a skewed, off-kilter wisdom, Perry remains engaging and highly watchable; there is, however, some bite to his buffoonery such as when he labels the Pope “a fake and a fraud” and humans as “cannibals” for the sin of consuming meat.

Whether it’s the sight of Perry performing an impromptu song about dead goats with two clown horns for the benefit of the filmmakers or his attempting to talk to a pigeon on Westminster Bridge, the unmistakable impression of a bona fide original remains. There are many sides and idiosyncrasies to Lee “Scratch” Perry and, in this sense at least, this freewheeling documentary is a fitting tribute.

Lee “Scratch Perry’s Vision of Paradie will be available on DVD via

Cadiz Music and on VOD via iTunes, Amazon Prime, Netfilx and the

film’s own website http://visionofparadise.de/vod on 8th April.

Scott Hammond