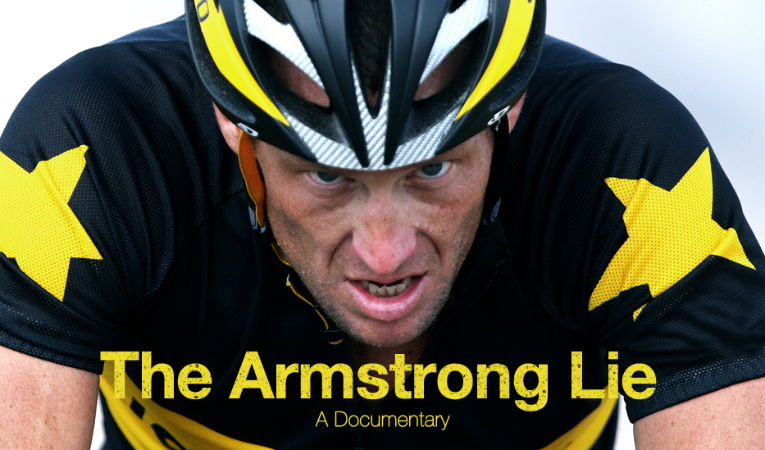

“It’s very hard to conceal the truth forever.” Just three hours after the bathetic formality of his Oprah Winfrey interview, these matter-of-fact words are spoken by disgraced seven time Tour De France winner Lance Armstrong to filmmaker Alex Gibney at the start of The Armstrong Lie; following a decade and a half of accusations, his unremitting games of denial simply couldn’t endure any longer. Originally setting out with the title ‘The Road Back,’ Gibney’s planned document of Armstrong’s 2009 comeback to cycling after a four year retirement had to be shelved due to a doping investigation in October 2012 that resulted in a lifetime ban and the UCI stripping Armstrong of all his Tour de France titles. Using the footage shot in 2009 along with new interviews to reshape the project in the aftermath of Armstrong’s admissions, Gibney’s documentary offers an intriguing insight into the downfall of a sportsman who attained iconic status worldwide, the intoxicating effects of mythology and the insidious culture of doping that spun an antithetical narrative that for years played within the shadow of the great myth.

“It’s very hard to conceal the truth forever.” Just three hours after the bathetic formality of his Oprah Winfrey interview, these matter-of-fact words are spoken by disgraced seven time Tour De France winner Lance Armstrong to filmmaker Alex Gibney at the start of The Armstrong Lie; following a decade and a half of accusations, his unremitting games of denial simply couldn’t endure any longer. Originally setting out with the title ‘The Road Back,’ Gibney’s planned document of Armstrong’s 2009 comeback to cycling after a four year retirement had to be shelved due to a doping investigation in October 2012 that resulted in a lifetime ban and the UCI stripping Armstrong of all his Tour de France titles. Using the footage shot in 2009 along with new interviews to reshape the project in the aftermath of Armstrong’s admissions, Gibney’s documentary offers an intriguing insight into the downfall of a sportsman who attained iconic status worldwide, the intoxicating effects of mythology and the insidious culture of doping that spun an antithetical narrative that for years played within the shadow of the great myth.

For those scornful of Armstrong’s lengthy deception and in the search for more evidence to fuel their contempt, the effect of The Armstrong Lie may leave a somewhat unsatisfying ambivalence. While the film displays many reasons for lamenting Armstrong’s character, the revelations as to the stark prevalence of performance enhancing drugs within his sport offer up a context of moral relativism whereby you can actually understand his reasons for taking them. Following on from the doping scandal of the Festina Affair in 1998 and subsequent to the US Postal Team’s united decision to “keep up with the Jones’” by utilising EPO, (a glycoprotein hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells) Armstrong’s first Tour De France victory in 1999 came within a climate of systematic abuse rife within the world of cycling; “You weren’t trying to beat the system, you were trying to be in the system” suggests former teammate George Hincapie.

We learn that, of all the cyclists who joined Armstrong on the podium throughout his seven successive tour wins, all but one were later implicated in doping scandals; this startling fact leaves no doubt that Armstrong was very much a product of a culture where such transgressions were commonplace.

What made Armstrong so exceptional, and what weaved the spellbindingly specious fairy-tale that captured the imagination of millions, was of course his overcoming cancer that had spread to his brain, lungs and abdomen. Also, it was this fierce battle for the highest possible stakes that imbued him with a ferociously competitive spirit where he would do anything to win, and as it turned out, do anything to protect the false veracity of his victories; “I like to win but, more than anything I can’t stand the idea of losing because to me that means death” he told Gibney in 2009.

So powerful was the story of survival and triumph that there were sufficient numbers, both within the cycling authorities and amongst a captivated public, to nurture and preserve the myth. Eager for a “tour of renewal” following the Festina affair, Armstrong’s victory in 1999 left Tour De France organisers with a problem; the fact that it was then the fastest ever tour would arouse suspicion yet they were in possession of possibly the most romantic figure in sporting history.

With this seductive tale of success in the wake of acute adversity, more interest, more fans and more money for sponsors and promoters started to roll in; there is no doubt that cycling as a whole had a vested interest in conserving Armstrong’s story. After a drug test in 1999 revealed traces of steroids in Armstrong’s urine, we learn that UCI president Hein Verbruggen approached US Postal’s managing director Johann Bruyneel to give him opportunity to explain away the findings; after a quick internet search, inadvertent use through the application of a cream for saddle sores was fabricated and the case was ignored.

The viewer can make up their own mind in regards to the fundamental ethics of Armstrong’s drug taking but it is in his cutthroat defiance and the ardent buying in to his own story that he becomes objectionable. With combative encounters with journalists and the callous treatment of those he believed to have wronged him, Armstrong’s truculent determination to succeed crossed the boundaries into ugliness. Using his financial might and celebrity to “bully” and “crush” his detractors, we hear Armstrong discredit Greg Lamond by attacking him for drink and drug problems and he undermines former US Postal staff member Emma O’Riley by labelling her a “whore.”

Armstrong protected himself with a modus operandi of constant suing for libel and a “my pockets are deeper than yours” approach to ensure the silence of his accusers. His obnoxiousness reached a peak in the tasteless exploitation of his cancer story; we hear him defend his innocence by stating that, by taking drugs, he would “lose the faith of all the cancer survivors around the world”; speaking in 2009, Armstrong claims to be embarrassed and sorrowful for these words but, after being such a convincing and profligate a liar for so long, it is hard not to see this contrition as further subterfuge to mitigate the severity of his behaviour.

With some beautifully cinematic views of Verbier in the Swiss Alps and the monstrous Mont Ventoux, the film’s latter moments take us to Armstrong’s return to the tour in 2009; this was a comeback that would ultimately prove his undoing. Former US Postal teammate Floyd Landis’ request of a place on Armstrong and Bruyneel’s Team Astana that year was a significant twist in the plot as his rejection by Bruyneel for being a convicted doper was, considering the team’s acceptance of Armstrong, too hypocritical for him to stomach; Landis knew the truth and the undertow of his resentment would eventually result in several of Armstrong’s peers breaking Omerta and spilling the revelations that led to his downfall.

Ostensibly returning to prove a point after years of persistent accusations, Armstrong’s performance at the tour merely resulted in more controversy. Looking unlike his old self and struggling to make the podium as the race entered its final stages, Armstrong’s astonishing recovery as he climbed the gruelling Ventoux and claimed 3rd overall position can almost certainly be explained by doping. A report in 2013 found an unnatural increase of red blood cells before Ventoux and, despite Armstrong’s claims of innocence, his words are nearly impossible to believe.

Similar to his struggle to compete clean as a younger man, it appears almost certain that Armstrong made the same deal again when, at 37 years old, he felt his capacity to succeed ebbing away. The UCI stripped Armstrong of his 3rd place finish and Armstrong’s protests serve merely as an updated lie in his litany of falsehoods. A criticism that has been levelled at The Armstrong Lie is the fact that the persistence of Armstrong’s mendacity render him all but redundant as an interviewee. While it is certainly difficult to believe anything he says, there is no questioning the authenticity of his conviction that, within the context of widespread doping, his seven Tour De France wins stand as valid achievements.

At the film’s conclusion, we hear Armstrong tell Oprah that the word “cheat” is defined as gaining an advantage over a rival and thus, not something he was guilty of. Gibney offers another definition and explains that “cheat” can also be equated with deception; Armstrong, therefore, undoubtedly cheated throughout his cycling career and Gibney’s film offers the unmistakable impression of a win at all costs sportsman regretful, not for the nature of his deceptions, but for his being found out.

By Scott Hammond