![]()

6th August 2016

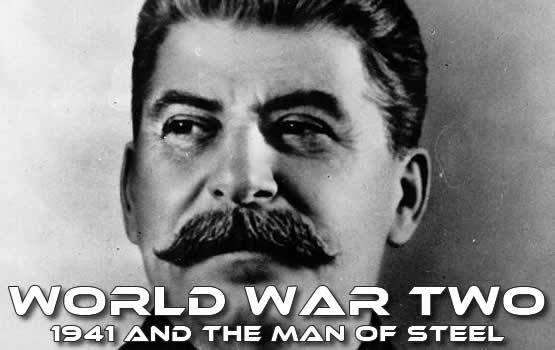

“He was a little man, about five foot five, in his 60s, rather tubby.” These opening words to World War Two: 1941 and the Man of Steel, paint a clear picture of Josef Stalin’s unlikelihood as an archetypal leader among men. The theme is revisited a little later in the film with focus on Stalin’s club foot, withered arm and – after his Georgian accent is compared to that of “Wigan Pier Lancashire” – a light-hearted segment where one of his speeches is translated with a George Formby-esque voiceover.

However, such superficialities are of course not instructive of a mind free of tyranny and murderous intention. In its thorough exploration of Stalin’s brutal character and dictatorship, a central theme of the film is the somewhat haunting irony that, in an attempt to assure its survival, Britain had to align itself with one of the biggest mass murders in history. In fact, what is argued here is that Stalin’s ultimately victorious role in the devastating life or death onslaught against Adolf Hitler was more crucial a factor in Great Britain’s survival than the Battle of Britain itself.

First screened on BBC Four on 13th June 2011 to mark the 70th anniversary of Operation Barbarossa – code name for Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 – and presented by Cambridge Historian David Reynolds, the film provides a compelling and comparatively rare perspective from the Russian side of the Second World War. It could be argued that any documentary film that dare delve into the subject of World War Two throws itself into impossible competition with 1973 masterpiece The World at War; however, where Thames Television’s 26 episodes and 22 hours were not quite enough to drill down into specific details of the myriad aspects of the conflict, what is offered up here is an excellent supplementary experience that sheds light both on Stalin’s leadership and his knack for shifting domestic and international allegiances to his advantage.

Described as a “gangster with a strategic brain” we learn that, to help fund the Bolshevik revolution in the dying years of Tsarist rule, Stalin was involved in a bank robbery that left forty people dead. This was indicative of a ruthless streak that became more pronounced after his consolidation of power following Lenin’s death in 1924. Stalin switched his political allegiances to eliminate his rivals and in subsequent show trials, abuses of torture and executions, betrayed thousands of the loyalists and officials who helped him rise. Arguably, the brutality of his rule culminated in the gulags of Siberia where millions were imprisoned and the forced collectivisation of agriculture that resulted in famine and the deaths of five million in 1932-3.

Some of the film’s most interesting moments deal with revelations in regard to Stalin’s near catastrophic military errors and, with Russia lurching from crisis to crisis, the dictator’s succumbing to something close to a nervous breakdown. Described by Reynolds as “one of the most spectacular military blunders in history” we learn that Stalin inexplicably didn’t even allow his commanders to start firing as millions of German troops crossed the Soviet border at the very beginning of Barbarossa. Also, he was guilty of misplaced deployments as the swiftly advancing Wermacht rolled into the Caucasus in the summer of 1942. However, the film later throws up an interesting analysis in the difference between victory and defeat: “Stalin learned from his military mistakes while setbacks made Hitler more unyielding in his fantasies”.

The most compelling aspect of the film is in its covering of the uncertain, unstable but ultimately imperative relationship between Stalin and Winston Churchill. Stalin grew impatient as Churchill stalled on launching a second front in Western Europe while continually strained relations could’ve resulted in a pact between Stalin and Hitler that would’ve surely been the death knell for Great Britain. We’re provided fascinating insight into the first face to face meetings between Stalin and Churchill, including a very interesting account where the icy deadlock between the two men was broken after Stalin invited Churchill to a wine-soaked six hour feast at his family home.

Reynolds is requisitely enthusiastic and engaging in his presenter role as he delivers narration from the present day sites of some of the narrative’s key locations. His playing out of some of the historical dialogues – particularly in the case of a phone conversation between Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev – are perhaps a tiny bit corny but by no means detract from the film’s focused documentation. Even the George Formby interlude manages to be a charmingly humorous moment rather than what could’ve easily been a failed incongruity.

World War Two and the Man of Steel is an engrossing and well-presented documentary film which utilises archive footage and photographs along with original telegrams and official documents to adroitly bring its story to life.

World War Two: 1941 and the Man of Steel is available on DVD from Monday 8th August.

Scott Hammond