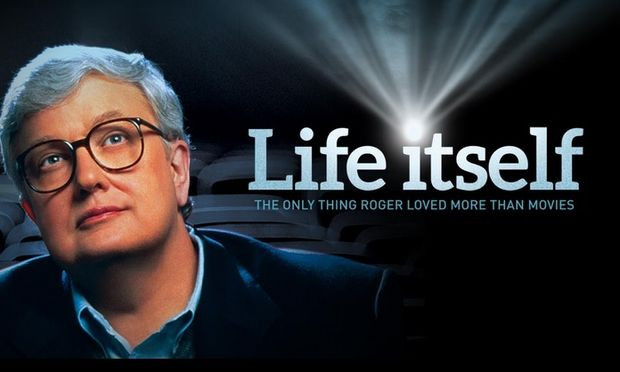

Almost twenty years after American film critic Roger Ebert gave a powerful kick-start to Steve James’ nascent career by declaring his wonderful documentary ‘Hoop Dreams’ as “one of the best films about American life I have ever seen”, James had the chance of returning the favour in his directing of ‘Life Itself’, a film on Ebert’s life faithfully based on the critic’s 2011 memoir of the same name. A deviation from his usual empathetic observational technique, James uses the solid framework of Ebert’s lauded memoir to create an absorbing biographical film at moments entertaining and funny while at others poignant and tender.

Almost twenty years after American film critic Roger Ebert gave a powerful kick-start to Steve James’ nascent career by declaring his wonderful documentary ‘Hoop Dreams’ as “one of the best films about American life I have ever seen”, James had the chance of returning the favour in his directing of ‘Life Itself’, a film on Ebert’s life faithfully based on the critic’s 2011 memoir of the same name. A deviation from his usual empathetic observational technique, James uses the solid framework of Ebert’s lauded memoir to create an absorbing biographical film at moments entertaining and funny while at others poignant and tender.

‘Life Itself’ oscillates between Ebert’s present day struggles with illness (a multiple cancer victim, he lost the ability to eat, drink or speak when his lower jaw was completely removed in 2006) and a retrospective account of his life. Using archival footage, photographs, interviews and passages taken from the memoir, we follow Ebert’s life from his beginnings as a precocious writer for a student newspaper in Illinois to his arrival at the Chicago Sun Times in 1967; a case of serendipitous timing as, on the cusp of a golden age of Hollywood filmmaking, the paper’s film critic retired and Ebert’s destiny was set on course.

Though he became the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1975, this was during a period of Ebert as an almost daily barroom drunk and raconteur that later resulted in his succumbing to alcohol and depression. This taste for hedonism (and quite possibly “boobs” as one of Ebert’s former colleagues suggests) was perhaps the driving motivation for his desultory choice to write the screenplay for Russ Meyer’s haphazardly lubricious romp ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’ in 1970; a film of which we hear a good natured Martin Scorsese amusingly struggle to deliver anything approaching a positive critique.

After Ebert’s last drink in 1979, further opportunity arose when his television show Sneak Previews, hosted alongside his Chicago Tribune adversary Gene Siskel, went national in the form of At the Movies. It is in the prominent featuring of the television show and, thus, Ebert’s relationship with Siskel that James largely deviates from his source material. While Ebert’s memoir reads as a tender recollection to his late friend and partner, James offers ample evidence of a relationship that, at best, could be described as having been complex. A rivalry fuelled by a seemingly sibling like competitiveness resulted in fiery on camera arguments and even childish demands that the names Siskel & Ebert should be alternately transposed for each broadcast of the show. In clear manifestations of a mutual dislike, the hilarious scenes revealing the off-air bickering between the two critics deliver the film’s funniest moments.

While the film has its fair share of light-heartedness, the present day scenes in Ebert’s hospital room are tinged with a profound sadness and contain occasional moments that are actually difficult to watch; we see, for instance, Ebert undergo a visibly painful suction procedure in order to clear saliva from his throat. Commendably, James manages to achieve success in this uneasy balance of the humorous and the heartrending. What is particularly striking, aside from Ebert’s courage in allowing such public access to his physical decline, is his admirable maintaining of good spirits throughout his health struggles. We hear him use a speech synthesiser to joke with visitors to his bedside, utilise a comical glance to camera when his wife Chaz accidently spills the beans on a medically unauthorised escape to the cinema and an amusing reaction upon his receiving the gift of a Lady Gaga toothbrush.

Evidently, there were two main reasons for Ebert’s bravery and continual fight for survival: Chaz, a remarkable presence of strength and kindness throughout and the subject of Ebert’s most touching words – “her love was like a wind pushing me back from the grave”. The other was writing; fully embracing the internet and social media, Ebert escaped into a world of movies, blogs and reviews and this provided him with a voice right up until his final days.

We are left with a view of Ebert as someone who reached unprecedented levels of fame for a purveyor of film criticism. In this age of televisual decline and accessibility to an online world where seemingly everyone has an opinion, it is now almost inconceivable that a critic could attain such ubiquity. Much of the footage we see in ‘Life Itself’ therefore speaks of a long-lost time where Ebert, along with Siskel, wielded a populist influence that could make or break a movie’s impact. James’ film includes both sides of the argument in relation to the Siskel & Ebert phenomenon: while we hear opinion that they created a deleterious climate of supposed movie criticism serving as little more than bite size consumer advice and a vehicle to “valorise huge films and eliminate the competition”, there is countering evidence that the duo actually engendered new talent and provided a platform for the underground; such endorsements saw the emergence of the likes of Michael Moore and Errol Morris, along with shoestring budget films such as Ramin Bahrani’s minimalist masterpiece of Sisyphean struggle ‘Man Push Cart’.

‘Life Itself’ is a touching portrait of a man who was the definitive mainstream critic in America. The combination of Ebert’s powerful memoir and James’ clear respect and passion for his subject and source material makes for an engrossing two hours of documentary film. Funny, sad, inspiring, poignant, hopeful and hopeless, James’ film is a rich tapestry only fitting of a life so thoroughly lived.

8/10

Scott Hammond

We have two DVD copies of ‘Life Itself’ to give away – why not enter our competition?